Few of the hardened gamblers that ever step ashore in Macao will ever venture into the historic quarter at the centre of Macao Island – but here lies the tale of the passage to Mammon that they have all unwittingly followed.

There are numerous visual clues that trace the history of Macao, both in its people and its architecture but a leisurely walk along a relatively straight but undulating mile will encapsulate much of the cultural journey that has sculpted Macao into the money obsessed city that it is today.

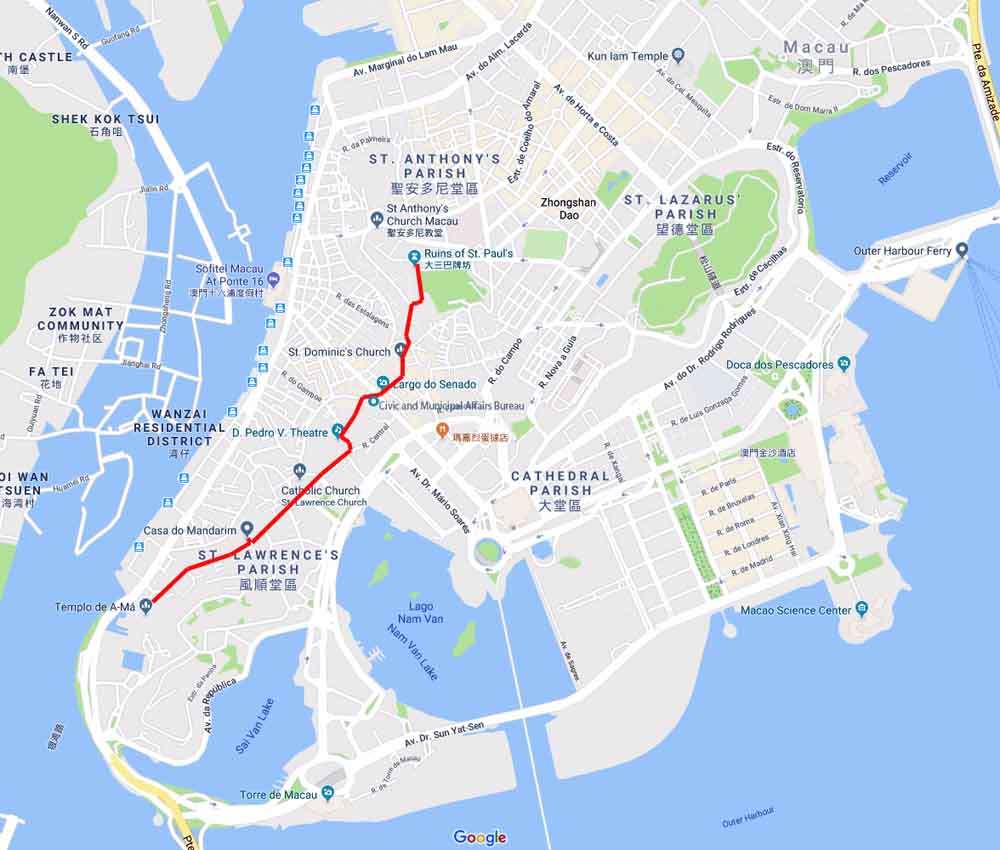

In a ragged line that runs from the south west to the northeast of the old quarter, as shown in red on our map, you pass through the centuries and the DNA of Macao’s history.

Starting in Barra Square you’ll find the A-Ma Temple dedicated to Matsu, the goddess of seafarers and fishermen.

Built in 1488, during the Ming dynasty, A-Ma is one of the three principal Buddhist halls in Macao. The temple is believed to be the namesake of Macau – a derivative introduced by the first Portuguese sailors who landed on the islands.

As the oldest building in Macao, with its poems and inscriptions, it provides an excellent introduction to Chinese culture during the birth of settlement here.

Strolling northwards it’s not long before you come across the ‘Mandarin’s House, or Zheng Guanying’s house.

Believed to have been started in 1869, Zheng’s house represents one of the first examples of a fusion of architectural influences from western cultures; making it a unique product of Chinese and western cultural interchange, charting the gradual integration of Portuguese and wealthy Chinese styles.

Noted as a reformist and theoretician Zheng wrote the commonly acknowledged masterpiece of Shengshi Weiyan, or – ‘Words of Warning in Times of Prosperity’. How prophetic, given the headlong hunt for wealth that was to become instrumental in Macao’s future.

The house itself is a fascinating collection of rooms and courtyards, where it’s easy to see the mix of Cantonese and Western styles blending together in harmony. You can easily spend an hour walking around its quiet hallways and rooms before once again heading out into the street and moving north once more.

Spend time to glance to either side as you do; as many of the side streets reflect the transition of less monumental architectural style; from the quaint and refined woodwork of Cantonese homes, ultimately through to the stacked concrete boxes of modern Macao.

Spend time to glance to either side as you do; as many of the side streets reflect the transition of less monumental architectural style; from the quaint and refined woodwork of Cantonese homes, ultimately through to the stacked concrete boxes of modern Macao.

Although built in 1560 and therefore slightly out of step with the convenient date chronology of our walk, St. Lawrence’s church is the first example of Catholicism that shows itself on our walk and in Macao for that matter.

Its Baroque architectural style over classical European marks a significant change in the architecture of Macao and the influences that began to make themselves felt with the occupying Portuguese.

Also known as ‘Feng Shun Tang’, or Church of Smooth-sailing Wind, it reflects the same ethos as that of A-Ma Temple in that St. Lawrence, the Portuguese patron saint of navigation, guides and protects sailors on the seas.

Pass by the imposing neo-classical façade of Dom Pedro V Theatre; built in 1860 by the Portuguese to commemorate their king. It has the accolade of being the first western style theatre in East Asia and as an important landmark is still regarded as a focal point for the arts and public events by local Macanese.

We’ve included the rather dry-sounding Civic and Municipal Affairs building, or IACM as it is now known, as being of some significance. Fronting the Lago do Senado (Senate Square) it was built in the late 16th century and was called the Senado, being used for senatorial meetings of the Macao local authority. More recently it was the office of the municipal administration authority, and now is the headquarters of the Civic and Municipal Affairs Bureau (IACM), all of whom have had a hand in Macao’s transition to a money-centric gambling fest.

The building was initially of brick and stone construction with a walled Chinese-style courtyard; later redeveloped in 1784 into a two-storey building in the baroque style.

After many years of deterioration, it was reconstructed in 1876 in neoclassic style, with a distinctive Portuguese 18th century mansion feel to it. Typhoon and termite damage apart, it has been maintained since as part of the Macao UNESCO World Heritage site.

Take the time to walk through the gardens and upstairs to the Grand Hall as the narrative of its history can be seen in many of the features.

You’ll now walk across the road and into the grand and impressive Senate Square; past the European styled building facades and along the waves of, more recently laid, alternately coloured ‘Portuguese pavement’ and on into the linked St. Dominic’s Square.

St Dominica is notable, not only for its striking colour scheme and baroque construction with Macanese features but also for its chequered history of violence.

Firstly it gained notoriety for the murder of a Spanish officer at the foot of its altar during mass, by an angry mob, for his refusal to accept Portuguese sovereignty over Macao – and latterly for its friars who barricaded themselves in and hurled rocks at besieging soldiers sent to uphold the Pope’s view on Chinese Confucian Rites – not being in parity with those of Catholicism.

Having been closed and expropriated by the government in 1834 it became barracks, a stable and subsequently government offices before finally being returned to its former glory as church.

As we move away from the 18th century and further north, the side streets become increasingly squalid and utilitarian, whilst buildings of significance tower around them, highlighting the disconnect created by wealth.

This culminates in your arrival at the ruins of St. Paul’s, which now stands as if some bedraggled Hollywood film-set facade. With the decline of Macao in favour of burgeoning Hong Kong as a trading port, the magnificent church also declined and was ultimately destroyed by a fire during a typhoon in 1835.

It stands as a poignant reminder perhaps, of the last vestiges of order and discipline before the rampant growth of Macao as a gambling mecca.

Stand at the top of the steps under the towering solitary southern façade, beneath the stature of the Virgin Mary standing on the seven-headed hydra.

As you look across the skyscraper casino skyline of Macao you can’t help but think that this ruin symbolises the failure of (as the Chinese characters under the statue suggest) ‘Holy Mother tramples the heads of the dragon’; the resolve and ability for which has crumbled in the face of the three dimensional monoliths to Mammon – as has the now two-dimensional building.

However philosophical you wish to be – and however dedicated a gambler – its well worth taking the heritage trail through old Macao. Even if you only do the simple route we’ve explored here, you’ll gain a perspective and insight into Macao’s history that no amount of looking for inspiration in the cards will bring.

If you simply want more information about getting to Macao from Hong Kong by TurboJET then follow the link here but why not ask us to arrange your own tailor-made travel throughout the Far East?

Let us plan your own inspiring journey to the Orient and Far East

Let us plan your own inspiring journey to the Orient and Far East

Why not download the TLC World guide brochure or give us a call today on 01202 030443, or simply click ‘enquire’ to submit your own personal itinerary request