By far the best way to explore Namibia is by self-drive. It gives you the freedom and independence to detour, pause or short-cut any aspect of your itinerary as the mood suits – and if you’ve pre-booked your accommodation, which is essential in high season, at least you know you’ve got a luxurious place to rest your head at the end of each day.

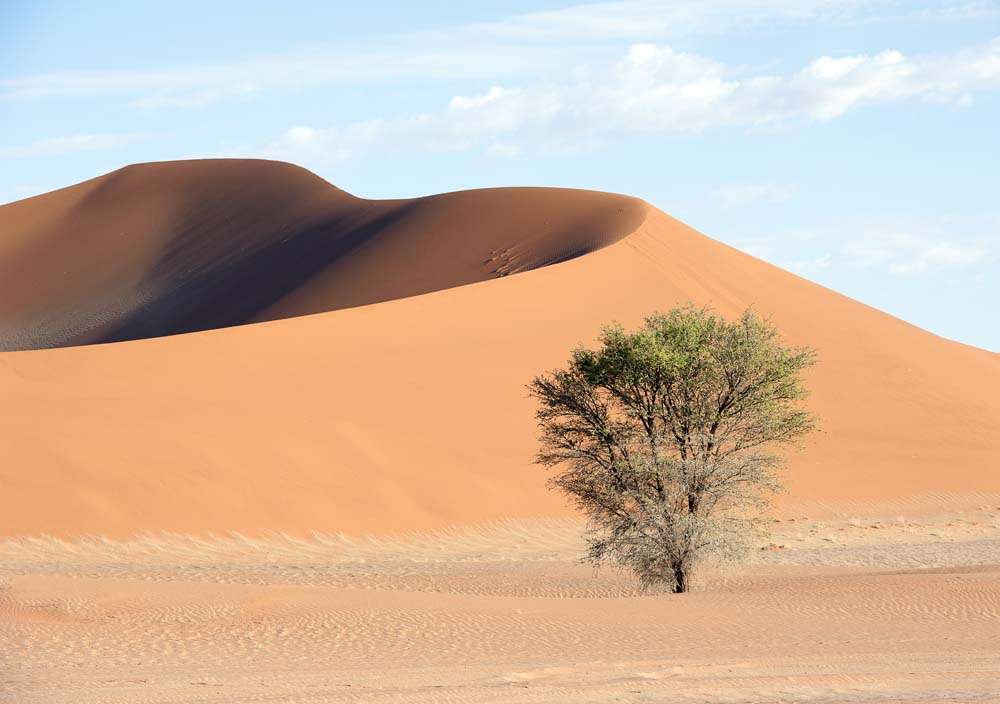

We chose to circumnavigate the whole country over three weeks and did so in a clockwise direction in order to include as much of Namibia’s diverse scenery, landscapes and wildlife as possible. Every day contributed in some way to the adventure but, for us, the following ten locations really added to the rich tapestry that is Namibia.

Many travellers spend less than three weeks in country, so our summary might help you to decide what your own priorities are if you choose to start your own adventure.

The Kalahari Desert – people and strange places.

No sooner have you headed south from Windhoek than after a few miles the black metal road gives way to compacted gravel and sand and further evolves into a sea of red sand on either side of the rudimentary roads. Caused by ionised magnetite blown from the north the red sands are both incongruous and magnificent.

At Intu Africa Kalahari Reserve, we stayed in one of the few areas where the rolling dunes are laced with thorn bush and acacia trees that fragment the otherwise monotonous vistas of sand. It’s here we had the opportunity to meet the San bush people who shared their ancient bush lore and culture with us before we progressed south towards Fish River.

Passing south of Mariental the Weissrand escarpment, cut by Fish River, runs parallel with the road until nearing Keetmanshoop where we turned off to find the Quiver Tree Forest, a dotted landscape of seven metre high aloes that form a forest amidst a rocky terrain of volcanic extrusions.

No more than a mile away is the even more bizarre Giant’s Playground, which as the name suggests, is like a Giant’s playroom where his volcanic building bricks have been scattered at random and have come to rest in strangely stacked piles of differing height that stretch as far as the eye can see.

Fish River Canyon – jaw dropping dimensions.

The second largest canyon in the world, Fish River Canyon, within Canyon Park is accessible over a very broken and uneven road that meanders in long sweeps through a landscape more akin to the Arizona desert with flat top Mesa-like escarpments at the periphery of your vision.

Nothing prepares you for your first sight of the canyon itself which irrespective of time of day, is an awesome spectacle of nature’s power and an immediate reminder of Man’s insignificance.

Trekking, driving or just chilling out are all valid options at Fish River Canyon but whatever you do it’s well worth the time.

Aus – Garub Wild Horses.

It beggars belief that anything, let alone horses, can survive in this bleached and arid Namib Desert landscape. It comes as little surprise therefore that although the existence of these horses is largely attributed to escaped colonial or farmed stock that some help is given towards their continued welfare in order to survive in the wild. Numbers tend to average around 100 as a sustainable number and although you might see them individually along the road heading north to Luderitz its very easy to miss the ‘Garub wild horses’ sign on the B4 that is little more than a sandblasted minor road sign.

This track leads you to a sun shelter and artificial waterhole where most afternoons will see a gathering of horses and their foals.

Whilst we tend to be sceptical of these artificial methods of presenting attractions to tourists, the likelihood of seeing the wild horses in any number otherwise fades when you contemplate the vastness of the surrounding desert – and the water does provide a very scarce resource for the animals.

Kolmanskuppe – Diamond miner’s ghost town

Depending on whether an abandoned German mining town in a wind-whipped depression holds any magic for you, Kolmannskuppe will either intrigue or bore you. Personally we found the notion of a community being abandoned and relocated by the lure of richer diamond seams quite interesting as the buildings are remarkably well preserved and the barren diamond studded landscape surrounding it is still protected by the current owners, De Beers.

Whilst our official guide seemed more disinterested than some of the visitors, he did at least establish the earlier fabric of life in the town, which our own imaginations were able to supplement; with the help of some of the artefacts in the town’s shop and the little delivery train who’s rails now disappear into the ever-encroaching sand.

The constant sand-blasting that we endured whilst visiting Kolmannskuppe made us wonder how anyone – engineers, workers, wives and children – could have sustained life here and still retained their sanity.

Luderitz – colonial architecture in Namibia’s second largest harbour.

The surroundings of Luderitz can have changed little since Bartolomeu Diaz came ashore in 1487 and as it’s the only area of rocky shore in the wasteland between desert and ocean became a natural choice for building one of the only towns on the Namibian coast.

Growing largely through trade especially, latterly, the mineral and diamond frenzy of colonial Germany and South Africa, Luderitz bears the clear imprint of their early twentieth century architecture that is remarkably well preserved and maintained. With the decline of the diamond fields near Luderitz the town has lost its trading strength and remains largely of interest to travellers.

Find your way to the Goerke house and Feldkirche church on the hill above the town to get an impression of the commitment and care invested in developing a life in these inhospitable places.

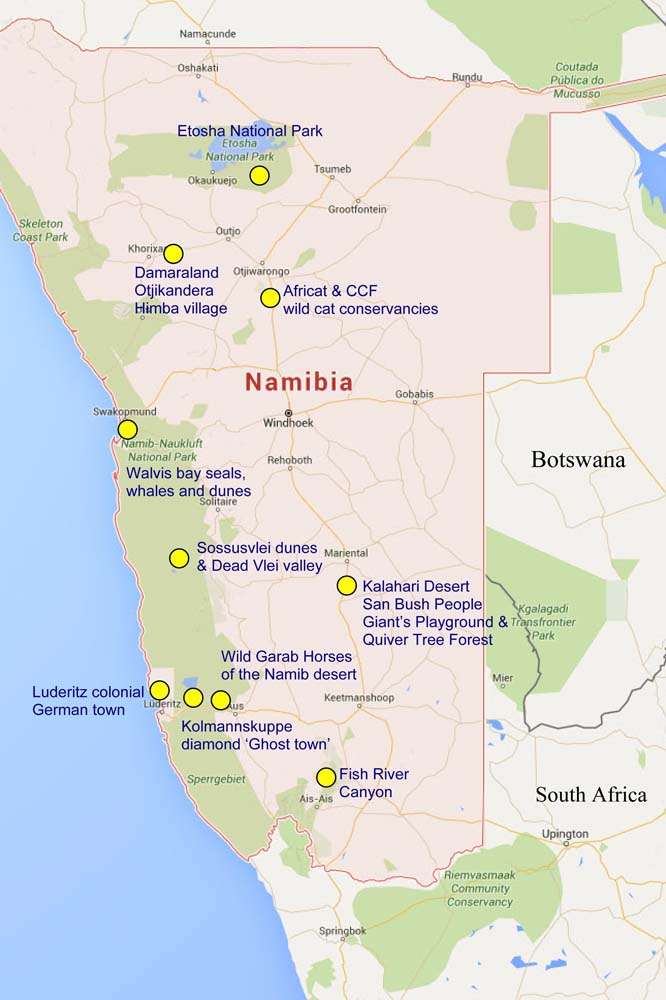

Sossusvlei – towering dunes and parched pans.

In the heart of the Namibian Desert lies the Namib-Naukluft Park and the towering red dunes of Sossusvlei and the parched pans of Dead & Hidden Vlei. The Park opens at sunrise and it’s well worth being there when the gate at Sesriem opens as it’s a 64km drive on metalled road to get to the Vleis. Not only will you benefit from the cool of the day but also the dramatic sun and shadow light contrasts of the early rising sun on the dunes, some of which are three hundred metres (nearly 1000ft) high.

Many stop at Dune 45 (not unsurprisingly, 45kms along the road) to climb the knife edge of this massive dune but if you do you’ll be sharing the Dead Vlei pan and its adjoining dunes much later at the end of the road with a far greater number of people in the rising heat. You can always return to 45 on the way out if you’re still keen.

There’s a car park at the end of the metaled road where you can take open jeep taxi trips over the last 5kms of deep sand; or if you’re driving 4×4 then you can drive yourself. We did pass a number of stranded vehicles that had been abandoned by their hapless drivers – so be warned – it’s not difficult but just requires technique.

When you reach the end of the sand tracks there are no obvious directions as to which way to go – and unwittingly we chose the more scenic route to Dead Vlei by climbing the knife edge of the huge dune to the left of the car park. It takes about twenty minutes to get to the top and instead of it being a route to Dead Vlei we saw it laid out a few hundred feet below us in the valley. There’s no way to go but down; so we literally sand surfed to the bottom of the dune, keeping the weight in our heels until reaching the parched and barren pan below. Our route is to be highly recommended as it gives you a unique perspective of the area, the pan and the surrounding dunes – plus its huge fun surfing the dune. If you’re unsure of heights then the drop on either side of you as you trek the edge of the dune on the ascent might give you a few anxious moments but its well worth the anxiety.

Dead Vlei – or Dead Pan – is one of Namibia’s iconic images, with skeletal dead trees amidst a parched grey/white salt pan that rarely sees water, surrounded by the highest red dunes in the country. Arriving early we were able to take pictures that didn’t have hundreds of others trying to take similar shots of the ‘deserted’ pan!

We made a schoolboy error on the way out by stopping for a snack in the shade of an Acacia tree. It was only when we saw the needle sharp thorns sticking out of the sides of our tyres that we realised our error. Fortunately we were able to remove them and reverse out without a puncture – amazed by how far the thorns will penetrate the rubber of the tyres.

Walvis Bay – sealife, sand life.

The largest harbour on the Namibian coastline, Walvis Bay’s main significance today is as a parking lot for currently idle oil industry rigs and ships who park more cheaply here than in neighbouring Angola.

As a recreational area it offers a number of exhilarating attractions; from 4×4 sand surfing on the mountainous dunes when groups of 4×4 vehicles brave the vertiginous slopes of shifting sand to bring your heart into your mouth before you’re offered oysters and wine to wash it back down again; to catamaran trips to seek whales, dolphins and seals, where once again any thought of sea-sickness is suppressed by beer, wine and canapes.

You need to be aware that whilst you can secure your own permit for driving the dunes, don’t expect to be rescued anytime soon if you become stranded. It’s definitely worth either joining a group tour or travelling in company with other suitably equipped vehicles.

Also consider that when on boats, sea fog is an ever-present possibility that at best can make it chilly (so carry a jumper) and worst case (although you’re perfectly safe in the official craft) was responsible for many of the wrecks along the Skeleton Coast!

Skeleton Coast – the bare bones.

Simply the name held a certain cachet for us over the years and provided one of the reasons for visiting Namibia at all. Strange really, as its one of the most desolate areas we’ve ever visited and has little to appeal about it except the all-pervading isolation of the place. Although much of the Namibian coast is referred to as the Skeleton Coast, the more recognised area lies within Skeleton Coast Park where you’ll sign a permit on entry and exit together with an understanding that you must enter/depart within certain times of the day.

The drive is generally straightforward across this seemingly boundless waste unless you choose to leave the gravel road and head towards the grey sea by way of the tracks that can easily snare the unwary driver with deep sand or razor sharp shales.

The coastline is scattered with the remains of ships across the decades, most of which are charted on the maps you’ll use to navigate. Wildlife is scarce albeit both lions and hyenas are supposed to inhabit parts of the coast – we saw neither. We did revel in being the only vehicle in sight as we cruised our way along the endless shoreline to inspect a wreck that now was little more than a rusting ribcage.

The appeal of the Skeleton Coast is in the realisation that you are driving through an area that has, for centuries, been notorious amongst mariners for the treacherous Benguela currents and fog which sent many to their deaths. Break down here and it could be a day before you see another car – so make sure you’ve adequate fuel, spare wheels, water and provisions should you be unlucky.

We derived more pleasure from the realisation that we’d driven the Skeleton Coast safely than we did from the sights of abandoned diamond mines and oil rigs along the way.

Damaraland – Himba people.

Time did not permit us to travel to the Angola border where the remaining tribal lands are concentrated but it did allow us to enter Damaraland on the way to Etosha in order to visit Otjikandero.

This village or reserve has been established primarily to provide home and work for orphaned children and their mothers of the Himba tribe, a sub-section of the Herero who were subjected to the first genocide of the twentieth century when a German military expedition slaughtered an estimated 70,000 in retaliation for anti-colonial uprising in 1904-5.

Although the experience is somewhat managed and contrived it nevertheless provides a fascinating insight into tribal life and customs and is well worth the visit.

The Petrified Forest, Twyfelfontain rock paintings and other geological features are in this area but we elected to take a rest day from driving rather than brave the 45 degree C heat amongst the hills.

Etosha National Park – wonderful wildlife wilderness.

Anyone visiting Namibia is likely to end up, or start their tour with time in Etosha National Park.

The park benefits from a freedom not often found in other countries in that you can drive yourself throughout the park using a perfectly reasonable guide and map book that you can purchase where you pay for entry. Better still is the practice of simply registering your vehicle number and driving straight into the park. This negates the need for lengthy registration and payment process at the gate at sunrise with the inevitable queues and delayed entry well after sun is up. This is particularly annoying in other parks because one of the golden hours of light for photography is immediately after sunrise – not a time to be queuing! Etosha solves this easily and it means that the payment process is speeded as vehicles have naturally spaced themselves out after a short drive into the park.

We’ll cover the Etosha experience in another more lengthy post but suffice to mention that we drove ourselves the full length of Etosha East from Anderson Gate to Von Lindequist Gate for the twelve hours between sunrise and sunset and then took a couple of shorter organised safari drives the following day. Each has its own merits – a toss-up between complete independence and that of inside information (as the guides are all in radio contact and pass the location of animals to one another).

Timing is important if you drive yourself for the first time as you can easily dwell for too long on animals at the start of your drive and find yourself missing other opportunities by scurrying to reach the exit gate before sunset. There’s a strict 60kmph speed limit to contend with as well, so some careful monitoring of progress is worthwhile.

It is possible to stay within the park but we felt the accommodation was more suited to backpackers and low budget travellers on the eastern side; albeit Dolomite and Onkoshi camps offer more upmarket accommodation at the western end, which our schedule didn’t permit time for.

Either way, the Etosha pans are unique and the collections of wildlife around the drying waterholes as summer advances ensure good viewing possibilities of animals in significant numbers.

Otjiwarongo & Okinjima – Cheetah Conservation Fund & Africat Foundation.

Depending on how interested you are in wild cat conservation will dictate which, if either, of these two worthwhile causes you visit and perhaps stay at. The Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) is dedicated to research and rehabilitation of cheetah, caught on neighbouring farmland, back into the wild. Africat, based in the Okinjima Nature Reserve is similar in its intent but covers a broader spectrum of wild animals including, cheetah, leopard and lion, as well as wild dog and their prey base.

In reality the likelihood of cheetah that are habituated to humans being released back to the wild are remote but Africat does have an extensive reserve area of some 20,000 hectares within which animals live and hunt freely. Some of these are radio collared which makes locating them somewhat easier.

Whatever your opinion of these organisations they should be lauded for the initiative that adds valuable protected land and habitat areas to National Parks, which by definition are limited in terms of dedicated areas for what wildlife remains on earth.

CCF does currently have limited but luxurious accommodation for anyone wishing to participate in the daily work of the fund, whilst Africat is much more commercially minded with several luxury lodges situated within their reserve.

Either location is well worth the visit, if not a stay as your presence will help towards the continuity of their valuable work.

We’ll cover the work of both in more depth in a later post.

If you manage to visit all of these and are happy with our choice we’d love to hear from you – at least you will have covered Namibia comprehensively and may have discovered other wonders on your travels.

Let us plan your own inspiring journey to Namibia and throughout Africa

Let us plan your own inspiring journey to Namibia and throughout Africa

Why not download the TLC World guide brochure or give us a call today on 01202 030443, or simply click ‘enquire’ to submit your own personal itinerary request

May 29, 2016

All places are awesome to visit. What about weather condition in Namibia. I think hot summer is not a good choice to have a tour.

May 29, 2016

Many thanks for your question. It very much depends on what you want to see as the various regions of Namibia experience variations of climate. We went in the month of November because many of the waterholes of Etosha have dried which concentrates game in those remaining, before any rain appears. Temperatures in the wet ‘summer’ season (November-March) peak at about 36 degrees and fall to about 18 degrees, whereas in the cooler and drier ‘winter’ season they peak at about 25 degrees and fall to about 8 degrees – so there’s not a huge temperature difference between wet and dry. We found that by travelling in November we got the best conditions for wildlife and the coastal and desert regions (which have good all year round weather influenced by either the African continent or Atlantic air streams – depending on where you are) – all areas can be accessed at most times of year. You might find some smaller roads cut off by flash floods in the wet periods but generally travelling in Namibia by car is exceptionally easy and the road conditions far better than other African countries. Bear in mind that most of your travelling will probably be within an a/c vehicle which minimises exposure to heat, if that is an issue. We hope this helps. If you’d like any assistance with planning a trip then contact cherrie@worldwideholidays.co.uk